Intro to Vanilla Policy Gradient

Theory and intuition behind one of our introductory algorithms

Vanilla policy gradient is one of the simplest reinforcement learning algorithms. It should serve to form the theoretical foundation for many following policy-based, online algorithms. If you’re more interested in offline algorithms, I recommend you start with TD-learning and deep Q-learning. See chapter 6 of Sutton and Barto for that.

This post assumes you’re familiar with how Markov Decision Processes work, and how the reinforcement learning problem is set up. For a guide to that, see here.

A bird’s eye view

Let’s describe what happens in a full iteration of the loop before diving in.

First, we collect a batch of trajectories \(\tau\) by allowing our current policy \(\pi\) (represented by a neural network) to unfold in the environment. We collect a full batch because, in general, the policy does not output actions \(a\), but a probability distribution over actions given the current state \(s\): \(\pi(a\vert s)\). To get to the next timestep in our trajectory, we select an action \(a\) by sampling from this distribution. Randomness may also occur as the result of the environment itself, so all in all we want to get plenty of samples to come up with an accurate, representative set of trajectories \(\tau\).

Sampling is great for blind exploration, but…

Eventually sampling doesn’t do the job any more. At some point we’ll want to exploit what we know and make our way to better states to be able to learn from there, so we’ll just pick the best known action instead of sampling. The amount of “greedy action selection” will be scheduled to increase over time, to progress from pure exploration of the state space to pure exploitation of the policy.

Now, if a policy gains an above-average sum of rewards in a particular trajectory, we will nudge the policy \(\pi\) in the direction of the actions \(a\) (given their respective states, \(\vert s\)) which resulted in this trajectory. Conversely, if a trajectory comes with a below-average sum of rewards, we nudge the policy away from taking those actions. This sum is known as the return for a trajectory

If any of this seems unclear, you’ll want to start with the previous post.

To estimate the return at each time step with low variance, we employ generalized advantage estimation (GAE). We train a neural network to represent the value function \(V\), which is incorporated into our advantage term \(A\). This will be discussed in the section on GAE.

Now, every time we go through our loop, we have a better estimate of what a good trajectory looks like (by training the value function \(V\)), and a better idea of what actions to take to get good trajectories (by training the policy \(\pi\)). This glosses over some details, which we’ll get into in just a bit.

Take a glance over the simplified pseudocode for the algorithm, then let’s get cracking!

Breaking down the policy gradient

The policy gradient is calculated as follows:

\[\hat{g}_{k}=\frac{1}{\left\vert \mathcal{D}_k \right\vert }\sum_{\tau\in \mathcal{D}_k}\sum_{t=0}^{T}\nabla _{\theta}\log\pi_\theta (a_t\vert s_t)_{\theta _k} \hat{V}_t\]Let’s break this down to gain an understanding of each term, working from the inside out. Let’s start with the policy:

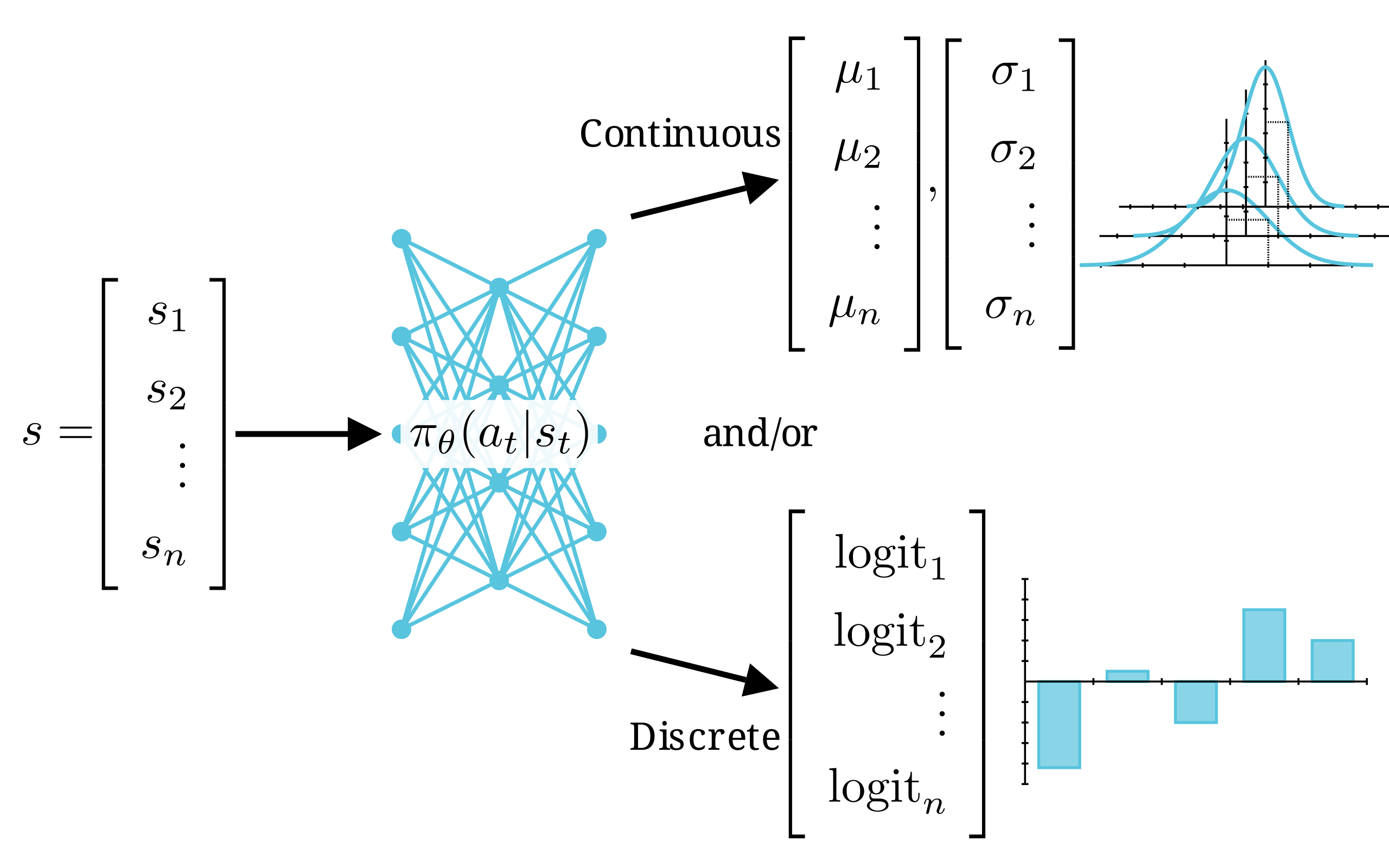

\[\pi_\theta (a_t\vert s_t)\]which is the function which outputs the probability distribution of all possible actions \(a_t\) at time \(t\) in the trajectory \(\tau\), given the state \(s_t\) at time \(t\). To bring it back to earth, think of this as \(y = f(x,\theta)\).

O_O

If this is making you feel like a deer in headlights, don’t worry. Let’s be more explicit. \(\theta\) parameterizes our function \(f\), and then we evaluate our function on \(x\). What do I mean? If I had a function \(y = f(x, \theta) = mx + b\), I parameterize this function with \(m\) and \(b\) (represented by the vector \(\theta = [m,b]\)), and then evaluate it on \(x\). In the case of a neural net, \(\theta\) is instead a matrix of numbers (which can be flattened into a vector \([a_1,a_2,a_3,...,a_n]\)) representing its weights and biases.

- If we have a discrete action space, this is a function which outputs a vector with a logit for each possible action (in other words, a categorical probability distribution).

- If the action space is continuous, this is a function which outputs the mean \(\mu\) and standard deviation \(\sigma\) representing the action’s probability distribution.

If you're worried about flexibility, it turns out you can also output arbitrary combinations of these, but we won't consider that case here.

Take the log of the policy:

\[\log\pi_\theta (a_t\vert s_t)\]Remember, all that is happening is we’re taking the log of a function, i.e., \(g(x, \theta) = \log(f(x, \theta))\).

Take the gradient of this with respect to the policy parameters \(\theta\).

\[\nabla_\theta \log\pi_\theta (a_t\vert s_t)\]Simply, the gradient of a function, i.e. \(\nabla g(x, \theta)\) with respect to \(\theta\).

Evaluate the policy given the current policy parameters \(\theta_k\):

\[\nabla_\theta \log\pi_\theta (a_t\vert s_t)\vert_{\theta_k}\]Or, we perform inference with the current model on the current state of the environment.

Numerical considerations

Let’s take a step back. If we are used to working out derivations with pencil and paper, the order in which I presented the last few steps should not start sounding any alarms.

Normally in this case one would take the derivative of the symbolic function, then evaluate that to get the derivative at the point of interest, or a similar method of your choice.

However, there are two differences when doing this numerically on your computer; having to do with the derivative and the log.

For the derivative:

Instead, we just say “hello, new best friend, the autodiff function

How does our new friend work? I’ll mostly defer to good explanations elsewhere, for example here and here. The gist is that first, it keeps track of the computation graph of whatever functions you want to differentiate, as you execute them, from state \(s\) and parameters \(\theta\) all the way to \(\log\pi_\theta (a_t\vert s_t)\vert_{\theta_k}\). Then, it uses this graph to multiply its way through the chain rule, resulting in the gradient(s) you want.

For the log:

For categorical distributions, it’s very simple.

We configure our neural network output to be logits, and later follow this with a softmax to convert to probabilities. We then simply compute the log of these values: \(\log \left[ P_\theta (s)\right]\).

Since this is a vector, to get the log probability for the action of interest \(a\), (\(a\) will be an integer from 0 to n-1, n being the dimensionality of the actions), we simply grab the \(a\)‘th value from this vector. In other words, we compute \(\log \left[ P_\theta (s)\right]_a\).

For continuous distributions, it’s a little trickier.

Remember we usually represent the probability distribution in the continuous case as a multivariate normal distribution. To keep things simple, we actually use a diagonal covariance matrix, rather than the full covariance matrix, so each dimension of the action can be represented by a single standard deviation. This way, we only need to output one mean and one standard deviation per dimension, and calculating the log of the distribution also becomes much easier. Now, how do we take the log of a (diagonal) normal distribution?

Like this!

\[\log\pi_\theta (a\vert s) = -\frac{1}{2}\left(n\log 2\pi+\sum_{i=1}^n\left[\frac{(a_i-\mu_i)^2}{\sigma_i^2}+2\log\sigma_i\right]\right)\]where n is the dimensionality of the action space. If you’re not convinced (I wasn’t), here’s a derivation.

Our neural network spits out a vector each of \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\), one element for each action dimension. With these values, we sample from a diagonal MVN distribution, yielding a vector of actions \(a\). Then, the above equation describes the log likelihoods of that vector of actions.

See here for reference.

Finally, summing this term over all time steps in our current trajectory gives us…

The meat of VPG

\[\sum_{t=0}^{T}\nabla_\theta \log\pi_\theta (a_t\vert s_t)\vert_{\theta_k}\]A brief derivation results in this full term, the grad log of the current policy. This term is the gradient of the probability of the current trajectory with respect to the policy parameters, evaluated using the current parameters. For that reason, let’s call this the probability gradient. (\(\nabla_\theta P(\tau)\), where \(\tau\) is the current trajectory).

In a moment, we’re going to add the \(V\) term we introduced in our bird’s eye view. Let’s review what we have so far without it: the probability gradient \(\nabla_\theta P(\tau)\).

- Without the sum over time steps (\(\nabla_\theta \log\pi_\theta (a_t\vert s_t)\vert_{\theta_k}\)), this tells us how much the probability distributions of our actions change, given a small change in each of our neural network parameters \(\theta\).

- With the sum over time steps (\(\sum_{t=0}^{T}\nabla_\theta \log\pi_\theta (a_t\vert s_t)\vert_{\theta_k}\) ), it instead tells us how much the probability of that sequence of time steps (the trajectory \(\tau\)) changes, again for a small change in our parameters \(\theta\).

This is great: if we want to change the probability of a particular trajectory (\(P(\tau)\)), we have the information to do that! (\(\nabla_\theta P(\tau)\))

The main remaining question is this: do we want our current trajectory \(\tau\) to happen more or less often? Well, I think we can agree, we want to make good trajectories happen more often, and bad trajectories happen less often. So how good (or bad) is our current trajectory?

Learning from rewards

The return \(R\) of a trajectory \(\tau\) is defined as the discounted sum of rewards obtained in that trajectory. The higher the return, the better the trajectory, and vice-versa. See the RL post for an intro to this concept.

Following directly from the policy gradient discussion above: we now know not only how to change a trajectory’s probability using \(\nabla_\theta P(\tau)\), but also whether to make it more or less probable: each probability gradient in the sum is weighted by the return \(R(\tau)\). That is, we have:

\[\hat{g}=\sum_{t=0}^{T}\nabla _{\theta}\log\pi_\theta (a_t\vert s_t)_{\theta _k} R\]which, again, tells us both how to change the probability of actions leading to the trajectory \(\tau = (s_0, a_0, r_1), (s_1,a_1,r_2), (s_2, a_2, r_3),…\), and now that we have the weight \(R(\tau)\), we know whether to make the action \(a_t\vert s_t\) more or less likely to happen. This summed over all time steps gives us the full policy gradient term.

Congrats! You’ve made it to the policy gradient!

If you stopped here, this rudimentary policy gradient would fit into our algorithm above, and that would be able to solve simple environments, albeit a little inefficiently. A golden retriever might eventually be trained to drive a car, but man, is it going to be hard going. And you know that he’s going to stop for treats and crash into mailmen.

No, we can do better than this. Take a breather, then let’s extend this picture.

Well, this is about a 15 minute read (or more) already.

Let’s wrap this up in the next post!