Imitation Learning with PWIL

An exercise on the Acrobot Swingup task

Motivation

Imitation learning

What can we do with imitation learning that we can’t do with plain RL? Well, there some situations in which it can help us out.

- We’re unable to adequately define a reward function for the task we have in mind.

- The reward function is known, but too sparse to learn efficiently.

- The reward function is adequate to learn to accomplish the goal, but it accomplishes it in an undesirable way.

We’re going to focus on the last situation for most of this post.

What do we have without IL?

The learned policies may be idiosyncratic. Perhaps they are too jerky, or do things that look obviously goofy or energy-inefficient. For instance, take a look at the RL-trained humanoid running in the video below. You should get the idea after 30s or so.

The “arm pumping” in the above video is serving some kind of counterbalancing purpose, but we know intuitively that this behavior is not ideal. Suppose we want that not to happen: defining rewards to tamp down on undesired behaviors can become a tedious and never-ending game of whack-a-mole.

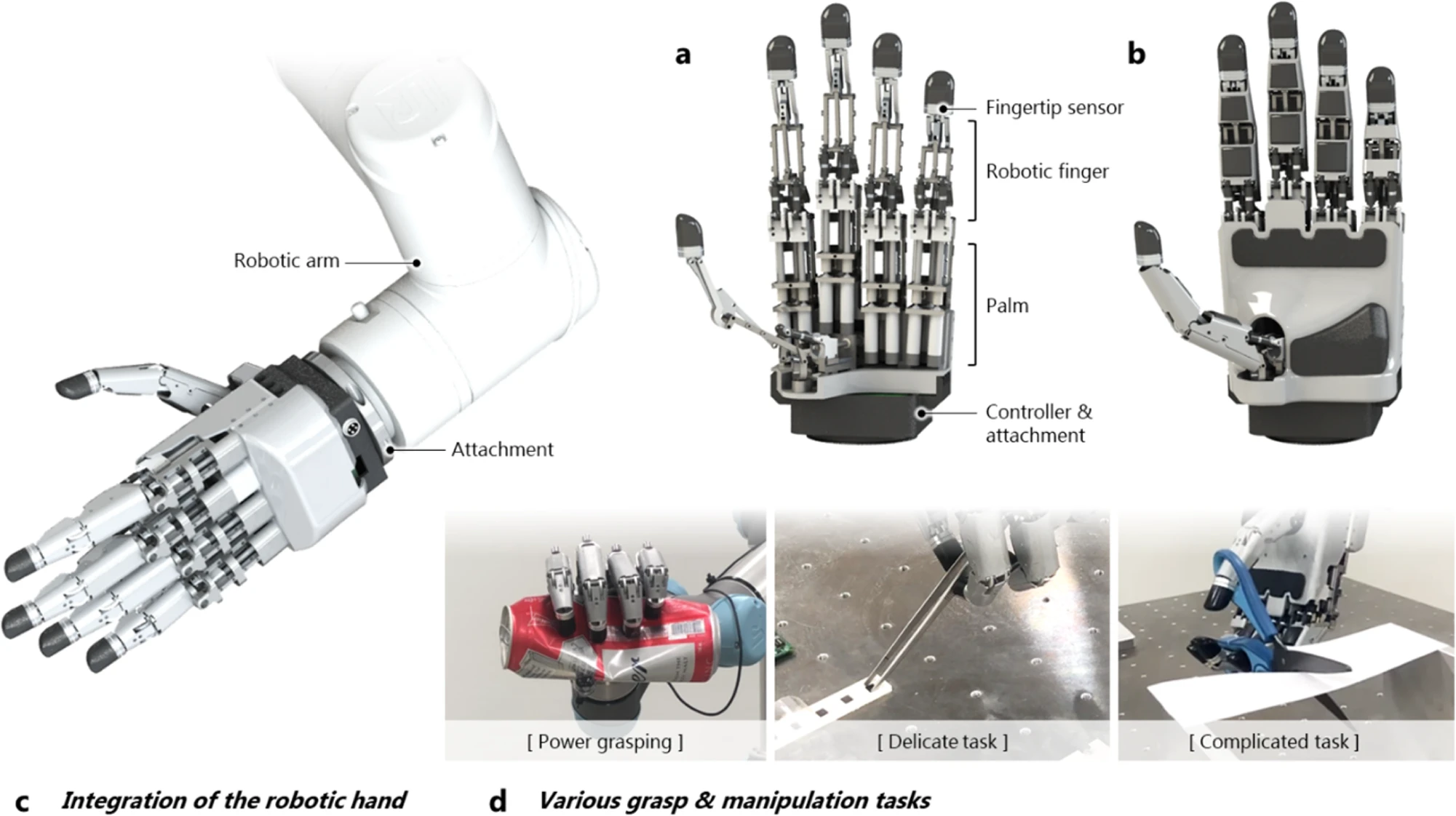

Another example: suppose I was training a robotic hand to grasp and sort objects of various size, material, and shape, certainly I would be able to specify distance-based measures of reward: how far is the object from the target? But the reward for a “stable grasp” of an object is not so easily mathematically defined.

Feature engineering?

Certainly we could get into the realm of feature engineering… perhaps I could define a stable grasp to be three points of contact at which I am applying a normal force, the sum of these forces being as close to zero as possible, all while relying on friction and torque as little as possible. Add in a feature for whether the center of gravity is below all of my contact points, and we’re looking pretty good.

However, this sort of manual feature engineering tends to be object class-specific. The features for grasping a glass of water will look very different from those for grasping a raspberry, a sheet of paper, a block of agar, or a chicken egg. This could also end up needing quite a few more sensors than we have available, rather than the usual image and/or robot state observation. Currently access to this kind of hardware shouldn’t be assumed, however, including force sensors in our observation will hopefully become the norm.

Avoid feature and reward engineering!

So, instead, we could have people moving the robot with a handheld controller to perform the desired tasks, record the camera images and control actions, and do imitation learning on these “expert demonstrations.” For the humanoid example, perhaps we could have people navigate obstacle courses while wearing motion capture gear.

There are of course other methods which we could use on this problem, such as RLHF, and more advanced methods which build upon what’s discussed here, but let’s stick to imitation learning for this post.

The Project

Solving the Acrobot environment

With all this motivation out of the way, let’s get going.

If you’re unfamiliar with Acrobot, it’s a classic control problem in which the “elbow” joint can be actuated, the “shoulder” joint swings freely, and the goal is (typically) to swing to a vertical, upwards position, starting from a vertical downwards position. Sometimes the goal is to also maintain this upright position, which we’ll leave for another time.

This may come as a shock, but there exist pretty good solutions to this problem that don’t involve deep reinforcement learning. ILQR, or the Iterative Linear Quadratic Regulator Algorithm, is among the best. See here for a good explanation. Qualitatively, one thing it seems to be good at is swinging up in a natural, expected fashion. In a real robot, we want to avoid high torques, high velocities, and high jerk values, to avoid wear on the robot and stay within operating limits.

The basic exercise of this post is: can we learn a classical ILQR controller’s policy for solving acrobot-swingup with imitation learning?

We don’t use the standard gym/mujoco environments for this post, because they don’t lend themselves as straightforwardly to using classical controllers via access to their dynamics and kinematics (it is possible, I just haven’t implemented it). Instead we use this repo.

Before imitation learning, we’ll get a baseline with reinforcement learning.

D4PG Baseline

This uses the D4PG algorithm, and is straightforward as far as RL goes. No tricks here. Before getting into a discussion of results, let’s get some results with imitation learning as well.

Imitation Learning with PWIL

First, we collect trajectories from an ILQR controller for swingup. The environment terminates and resets once the top is reached within some tolerance. Taking inspiration from DART, since we have the option, we inject the ILQR controller’s actions with noise. We use envlogger to record trajectories to a Tensorflow dataset. Another option would be to store to Reverb with the same library, if you’re more familiar with that.

Next, we train PWIL on these collected trajectories for 1M time steps. Let’s take a look at the results…

By learning to imitate the classical controller’s actions given the state, this learned controller shows signs of life in its training curve. Because it isn’t training to maximize rewards directly (the loss function doesn’t even contain the environment reward), as expected, the final average return isn’t quite so high as something that’s optimizing for it.

Let’s visualize a rollout of the PWIL-learned policy.

It doesn’t mimic the ILQR controller perfectly; the torque actions are not so smooth in time, and the trajectory is not exactly the same. This was trained with two sources of noise: the ILQR controller itself had its actions and observations perturbed, and PWIL additionally perturbs actions. Because of this, the ILQR example may not be perfectly representative of that algorithms behavior. This said, the performance is surprisingly good; training on more demonstrations for more timesteps may mimic the original controller even better.

Discussion

Now at this point it’s worth discussing the reward and termination scheme.

Rewards

The environment gives a reward of +10 if the end of the pendulum is within some radius of the target (i.e. where the pendulum is completely vertical and pointing up; the angle of the first joint is \(\pi\) and the angle of the second joint is 0). The radius threshold is somewhat large: 0.2 (compare to the length of the pendulum: 0.5). In all cases it will receive an additional penalty proportional to its distance from the target, and penalties proportional to the absolute position and velocity, to avoid wild spinning.

Termination / reset

Finally, the environment resets either after 10 seconds (5000 time steps each 0.002s long), or if the end of the pendulum is both within the aforementioned radius from the target, and its y position is within 0.05 of the target. This y condition is most of the story, but the radius necessitates it to be nearer to the center.

There is a potential discrepancy in this setup: do you see it? Let’s take another look at the D4PG rollout.

The first loop goes to the target as hoped for; the second loop maintains position some distance from the target, below the y position. That’s strange… if we look more closely at the first loop, and notice that the position of the middle joint does not go to the top, we can see that the termination condition wasn’t actually reached! And indeed, looking at the episode length chart from training the D4PG agent, it is more or less always at the full 5000 time steps. Clearly the agent has learned to not terminate the episode, but get as many +10’s as it can while staying inside the target radius threshold, but below the y position threshold.

This is a perfect example of why visualization is so important.

What to do?

Let’s simplify the reward, so there’s no conditional +10. Let’s re-train both D4PG and PWIL with the fix. This should tamp down on the “hold near target” behavior, and the max return should be near 0. PWIL doesn’t use this reward to train, so we’re merely reflecting how the training on the same PWIL reward affects progression towards the fixed environment reward. We still expect the D4PG curve to end with a higher return, since it’s optimizing for the environment reward, however it should converge on some value just below 0.

While D4PG appears to have an edge on returns, PWIL is not far behind, and may catch up with further training.

The results

Now, our D4PG agent (as seen in the left gif below) shoots straight to the target. Our PWIL-trained agent, as before, takes a few swings to build momentum before its final approach. Note, the PWIL training / loss function never changed (it doesn’t see environment reward). This different result from the previous PWIL rollout is merely the effect of randomness during training, and acting during this particular rollout. If more care was taken to fix all RNG seeds through the entire process, we would expect the same result, to within numerical error.

Who wins?

So what exactly is the benefit of imitation learning? Looking purely at rewards, D4PG seemed to win out here. Just as well, it achieves the top position much more quickly.

Well, considering the two gifs above, let’s ask ourselves: which would we prefer to run on a real robot? If we’re concerned with robotics (amongst many other applications), we’re going to have to come out of the simulation into the real world at some point.

Taking into consideration the maximum torque a robot may be capable of, and the wear that may result from both high speeds and discontinuous torque commands in time (i.e., jerk), the PWIL agent starts to look more appealing. It uses a lower torque, the maximum \(\Delta \tau\) between timesteps (finite-difference jerk) is lower, and it achieves lower maximum speeds. Intuitively, one might describe this method as “more natural,” akin to the way we would expect a human gymnast to swing up.

The real world case for imitation learning

This last point is really the kicker for imitation learning. We know intuitively the “safer,” “natural” trajectory, but how does one go about defining all of these requirements into a reward function? We could penalize speed and torque, but we’ve done that already with D4PG, haven’t we? And the result is a high-speed, high-torque, unnatural policy. Perhaps there are a few features we’ve forgotten about, but at best, we need to figure out how to correctly come up with a weighting for each of the different reward components. An iterative approach to this “reward shaping” could quickly become tedious at best, intractable at worst. So, from this point of view, one may say PWIL has won this contest!

Finetuning a PWIL policy with RL

In the best case, we’d have motion capture data from real gymnasts swinging to an upright position, and could use this as our baseline for a natural, low-wear, efficient solution. We could then learn from that experience. That intermediary policy could then be fine-tuned with RL, requiring far fewer environment interactions, which are very expensive once we exit the simulator into the real world.

We have expert ILQR data doing much of just that. Can we fine tune on this PWIL result with RL? I did try this, but the results were less than satisfying. In summary:

- In a naive attempt to make use of the PWIL policy, I first filled the replay buffer with transitions from the existing PWIL policy, then turned on training in the real environment. This didn’t work; as soon as the training was enabled, the returns shot down, and did not recover their original values before the PWIL policy’s transitions in the replay buffer were replaced with online data.

- To mitigate the issue of starting with a value function which was trained for PWIL rewards, I instead trained the value function alone, without training the policy, to convergence. Unfortunately, once policy training was re-enabled, the original D4PG policy was quickly recovered, with no remnant of the PWIL policy. This shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise; we’re using the same reward function as for D4PG now.

Next steps

If one wanted to explore this fine-tuning idea further, I’d suggest to introduce another term to the finetuning loss function, to keep much of the expert-based behavior which we’ve so carefully trained on. One which penalizes, for example, the weighted Earth-Mover / Wasserstein distance, between our baseline PWIL policy and the new fine-tuned version. This way, we’d be able to only slightly optimize our existing policy towards some particular reward function.

However, we’ve come back into contact with the issue of shaping a reward function for your real-life robot. Avoiding this is a big selling point for imitation learning (alongside less random exploration, which was less of an issue for this simple environment). So, in the interest of continuing to avoid this tedious issue, one may also consider starting with this PWIL-trained agent, and applying Reinforcement Learning from Human Preferences.

If there is any interest, perhaps I will tackle these paths in upcoming posts!

Thanks very much for reading. If you’re looking to reproduce these results (with a bit of effort on your end), I’ve posted the code on GitHub here.